by Liscio

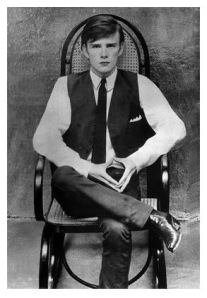

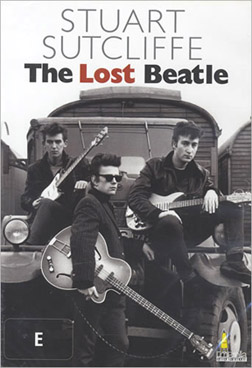

Shy and withdrawn, hardly able to play a chord, so unsure of his ability he hid behind dark glasses and turned his back to the audience—if this is your portrait of Stuart Sutcliffe, you’ve got the wrong rock bass guitarist.

Stu has been described as gentle, delicate, a boy of beautiful heart. But he was funny enough to be on par with Lennon. He was an original thinker, highly intelligent, responsible and mature beyond his young years, “vulnerable on the surface but extremely strong underneath”. He was innovative (painting in Hamburg with metallic car paint and charcoal) and daring—art master Arthur Ballard remembered in the Beatles biography, Shout, that against college rules, Stuart painted on massive canvasses and was a sartorial trendsetter even before Hamburg. Klaus Voorman said Stu could “see 10 times more than other people”—he was “miles ahead of everybody”, especially regarding the intensity of his life, his art, and his cutting-edge perception of style and imagery. An amazing profile for a kid barely out of his teens.

Stu has been described as gentle, delicate, a boy of beautiful heart. But he was funny enough to be on par with Lennon. He was an original thinker, highly intelligent, responsible and mature beyond his young years, “vulnerable on the surface but extremely strong underneath”. He was innovative (painting in Hamburg with metallic car paint and charcoal) and daring—art master Arthur Ballard remembered in the Beatles biography, Shout, that against college rules, Stuart painted on massive canvasses and was a sartorial trendsetter even before Hamburg. Klaus Voorman said Stu could “see 10 times more than other people”—he was “miles ahead of everybody”, especially regarding the intensity of his life, his art, and his cutting-edge perception of style and imagery. An amazing profile for a kid barely out of his teens.

But could he play the guitar?

The contention that Stu was “a bad bass player” is a piece of historical hokum that has no substantiation– meaning no factual evidence backs it up. Stuart had basically only two detractors: the statements of one have been shown to be blatantly false—the remarks of the other are inconsistent and less than impartial. Yet years of media repetition from these two sources have been accepted as truth.

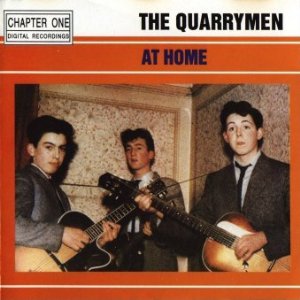

Let’s start at the end of 1959 when teenaged Lennon, McCartney and Harrison were actively searching for a bass guitarist. As is well known, they persuaded 19-year-old art student Sutcliffe to purchase a Hofner electric bass. George Harrison said it was “better to have a bass player that couldn’t play than to not have a bass player at all.” (1) Stuart straightaway recruited Dave May of the local Silhouettes to teach him Eddie Cochran’s “C’mon Everybody”.

The Forthlin Road rehearsals at Paul’s house, some of which were taped on Rod Murray’s (Stu’s flatmate) tape recorder, took place that March. In a 2007 article, Murray said, “Stu would borrow the recorder and go to Paul’s house to record…but he had to buy his own tapes as they were so expensive.” The audio quality is poor, but listening to these tapes makes clear that the entire band at this point was very rudimentary. (Note: Of the 16 songs known to have been recorded at the Forthlin Road rehearsals, three were released on 1995’s Anthology 1: “Cayenne”, “Hallelujah” and “I Love Her So”. You can hear these on Youtube).

The Forthlin Road rehearsals at Paul’s house, some of which were taped on Rod Murray’s (Stu’s flatmate) tape recorder, took place that March. In a 2007 article, Murray said, “Stu would borrow the recorder and go to Paul’s house to record…but he had to buy his own tapes as they were so expensive.” The audio quality is poor, but listening to these tapes makes clear that the entire band at this point was very rudimentary. (Note: Of the 16 songs known to have been recorded at the Forthlin Road rehearsals, three were released on 1995’s Anthology 1: “Cayenne”, “Hallelujah” and “I Love Her So”. You can hear these on Youtube).

Finding gigs in Liverpool was tough and everybody was still going to school; not having played much together “for months”, on May 10 the group found themselves before London musical scout Larry Parnes, who was looking for a group to back one of his stars, Billy Fury. Photos of this audition do show Stuart playing with his back turned, perhaps attempting to hide his fledgling ability. Paul McCartney said, “If anyone had been taking notice, they would have seen that when we were all in A, Stu would be in another key. But he soon caught up and we passed that audition to go on tour.” (2)

These photos are the only ones of Stuart playing turned around—and this is where one of the sources of the “bad bass playing” got its start.

The idea sprang from the lips of one Allan Williams, a colorful man of dubious veracity who called himself the Beatles manager when he was, in fact, a booking agent for various bands in Liverpool.

Bill Harry, art school classmate of Sutcliffe and Lennon and creator of Mersey Beat magazine, sets the record absolutely straight: “Allan Williams always comes out with the story that Stuart Sutcliffe played with his back to Larry Parnes at the Wyvern Club audition because he couldn’t play the bass, and that Parnes said he would take the group as Billy Fury’s backing group if they got rid of Stuart. This story first appeared in Williams’ book, ‘The Man Who Gave the Beatles Away’. Williams’ allegation is untrue. Parnes himself was to say that he had no problem with Stuart, that his objection was to drummer Tommy Moore, who turned up late for the audition, was dressed differently than the other members and was a lot older than them. When we used to book the group for the art school dances there seemed to be no problem with Stuart’s performance. In fact I never heard any criticism of Stuart as a musician until the publication of Williams’ book (which came out in 1977).” (3)

After returning home from their tour, the band played some twenty-odd venues around Liverpool before August 1960. At this time, one of Liverpool’s best, established groups was Derry and the Seniors. Seniors’ Howie Casey remarked for the ‘Beatles Anthology’, “they were a nothing little band.” When he heard the Beatles were soon to play in Germany, Casey complained, “They might destroy the [emerging German rock] scene. I said send a band like Rory Storm or the Big Three. When they did turn up, they were vastly improved…the improvement was like night and day.”

After returning home from their tour, the band played some twenty-odd venues around Liverpool before August 1960. At this time, one of Liverpool’s best, established groups was Derry and the Seniors. Seniors’ Howie Casey remarked for the ‘Beatles Anthology’, “they were a nothing little band.” When he heard the Beatles were soon to play in Germany, Casey complained, “They might destroy the [emerging German rock] scene. I said send a band like Rory Storm or the Big Three. When they did turn up, they were vastly improved…the improvement was like night and day.”

Arriving in Hamburg, the Beatles (whose current playlist of songs could barely fill an hour) were shocked to learn they were expected to play close to eight hours nearly every night. They had to expand their repertoire, and fast.

George: “We had to learn millions of songs. We’d be on for hours…Saturday would start at three or four in the afternoon and go on until five or six in the morning.”

John: “We got better and got more confidence. We couldn’t help it, with all the experience, playing all night long.”

Paul: “We got better and better and other groups started coming to watch us.”

Is it credible to think that all this learning, experience, confidence and improvement affected every Beatle except Sutcliffe—the others were roaring along, but Stu was still just plunking? Stuart himself wrote home: “We have improved a thousand-fold since our arrival.”

These “savage young Beatles” were now playing loud, thrashing, primeval and pumping proto-punk rock—a throbbing nightly musical orgy. Lennon would say these Hamburg performances were the Beatles at their rock and roll best.

“Backbeat” director Ian Softley, after researching extensively and talking to bands and others who attended the German clubs, told the Los Angeles Times: “he (Stu) was very punk, very insistent. He would turn up his bass really loud… it was dominant and driving.”

Howie Casey said in the same Times piece that Stu “had a great live style”. He would know…while the recently-arrived Beatles were still playing the Indra, Bruno Koschmider (owner of both clubs) wanted continual music at the Kaiserkeller. So he split up the Seniors and the Beatles–in effect, creating a third band. Says Casey, “I was given Stuart Sutcliffe along with Derry and Stan Foster and we had a German drummer.” If Stuart couldn’t play, a professional like Casey certainly wouldn’t have tolerated him very long. Casey never complained about Stu’s ability. And this temporary split actually made Sutcliffe the first Beatle to play the sought-after Kaiserkeller gig.

In ‘The Beatles History’, Rick Hardy of the Jets confirmed: “Stu never turned his back on stage. He certainly played to the audience and he certainly played bass. If you have someone who can’t play the instrument properly, you have no bass sound. There were two rhythm guitarists with the Beatles and if one of them couldn’t play, you wouldn’t have noticed it—but it’s different with a bass guitar. I was there and I can say quite definitely Stuart never did a show in which he wasn’t facing the audience.”

Renowned artist and bassist Klaus Voorman says, “Stu was a really good rock and roll bass player, a very basic bass player, completely different. He was, at the time, my favorite bass player…and he had that cool look.” In a 2006 documentary, Voorman’s opinion was, “The Beatles were best when Stuart was still in the band. To me it had more balls, it was even more rock and roll when Stuart was playing the bass and Paul was playing piano or another guitar. The band was, somehow, as a rock and roll band, more complete.”

Interviewed on radio, Beatles drummer Pete Best revealed “what a good bass player Stuart was.” Pete has said, “I’ve read so many people putting him down for his bass playing. I’d like to set that one straight. His bass playing was a lot better than people give him credit for. He knew what his limits were…what he did was accept that and he gave 200%. He was the smallest Beatle with the biggest heart.”

Stu, who had stayed in Hamburg after the others had gone back to Liverpool, received a letter from George that read in part: “Come home sooner, as if we get a new bass player for the time being, it will be crumby as he will have to learn everything. It’s no good with Paul playing bass, we’d decided, that is, if he had some kind of bass to play on!”

And not long before his death, after he’d left the Beatles, Stuart was asked to play with a German group, the Bats. He borrowed back his bass from Voorman (to whom he’d sold it), and played the Hamburg Art School Carnival and the Kaiserkeller. The “James Dean of Hamburg” was obviously respected for his bass work.

There is no record of anyone commenting negatively about Stuart’s playing the entire time the Beatles were actually performing in Liverpool or in Hamburg…except for one. At last we come to Stuart’s other detractor: Paul McCartney.

Paul has knocked Stu’s bass playing– remarks he made while working with Stu were perhaps spawned by their “dead rivalry” (at least that’s how Paul saw it), and are therefore open to question. But many of Paul’s negative comments have been in retrospect. In 1964, much closer to when he’d actually been playing with Sutcliffe, Paul said in a Beat Instrumental interview: “Not that I’m suggesting that every bass player should learn on an ordinary guitar. Stuart Sutcliffe certainly didn’t, and he was a great bass man.”

Stuart was clear-eyed and candid about his musicianship. He put it all out there and made no apologies. He had the nerve to audition when he’d barely begun to play—that took guts. He worked hard and grew in expertise along with the rest of the band in Liverpool. Having to quickly master new material in Germany, Stu could rely, if not on deep innate talent, then on his very high IQ to memorize the “millions” of new songs. Voorman gets the last word on the result: “It sounded amazing, fantastic. I loved it from the first moment. The other bands that played in the clubs were good, but none were as good as them.”

By all reliable accounts, Sutcliffe’s bass put down a hard-driving, rock and roll sound. It wasn’t fancy…his attack was pretty basic. But when it came to playing raw, exciting, sex-drenched rock and roll that hit you in the chest, electrified your limbs, made you want to dance all night and kept you coming back to the Top Ten Club for more, the band to see was Stuart Sutcliffe and The Beatles.

——

Sources:

(1) ‘A Brief History of the Beatles’ online

(2) ‘The Beatles Bible’ online

(3) ‘The Beatles History’ online

Note: Additional references for this article include: The Life of John Lennon and Shout by Philip Norman; quotes by Astrid Kirchherr for Boston 90.9 WBUR and How Stuff Works; Liddypool: Birthplace of the Beatles by David Bedford; The Beatles in Hamburg by Hillman; Art by Lennon, McCartney, Sutcliffe and Starr; interviews by Garry James; British Youth Culture-Shapers of the 80’s; The Quarrymen Through Rubber Soul by Everett; Pete Best interview/terrascope; Komm, Gib Mir Deine Hand by Knublauch, Korinth and Muller; Stuart Sutcliffe letters; Voorman/tripod.com Quotes; and John, Paul, George, Ringo and Stu-Los Angeles Times/Movies

June 24, 2011 at 9:51 pm

in other words …..he really didnt play bass all too well

June 25, 2011 at 6:53 pm

Ha! Ha! Exactly!!

September 20, 2011 at 1:06 pm

No the article is saying he could play the bass well, hence the reason Howie Casey was happy to let him play with his group. He wasn’t the greatest ever, but he was as good as many of the bass players of his day. seemed clear enough for me from the article?

April 7, 2023 at 2:57 am

That applies to Sid Vicious, not Stuart.

June 25, 2011 at 1:46 am

Quite a fascinating article!

June 25, 2011 at 5:47 pm

He was the precursor to Dee Dee Ramone, 10-15 years earlier!

June 25, 2011 at 11:12 pm

Great article! In October a stage version of Backbeat will open in London – under the title of ‘Twist and Shout’ – hopefully it will put the record straight on Stu as much as this article.

June 26, 2011 at 8:51 am

Stu boiled over as the “carrots and peas” background of the Beatles, playing a meaty cube of protein-spunk that had the bird’s knickers in a twist, his tantalizing bass aroma akin to huffing metallic car paint. To say that Stu could not play is to say that Stu played as if he could not play, a new sound of raw hardtack scouse fricassée that was a century ahead of the Beatle’s petering best. Oh, Stu played alright, turning his back on an audience too thick to grasp his polyrhythmic Death Metal (Note: see Sutcliffe’s original song “Aneurism” on 1996’s Anthology 9.) McCartney learned all he knew, and more, from Stu and should apologize to every Beatle fan individually!

September 9, 2013 at 5:46 am

here here hun, i agree. x

May 30, 2014 at 11:54 am

Paul should apologize to Beatles fans?, lol please

June 29, 2011 at 11:31 am

So the gist of this article is: Stu was a saint. Stu had no faults. Stu was brilliant at everything he ever did. Even his average bass playing was brilliant. What a load of revisionist hooey.

And Henry Fool: Bravo. That was an incredible bit of sarcasm and right on the money. Paul McCartney played the bass in ways that Sutcliffe couldn’t even begin to imagine. If anything, it’s the Saint Stu types who owe an apology to McCartney for consistently painting him as the villain. Get over it, already. If Stu had been good enough to be in the band and had wanted to stay in the band and if Lennon had wanted him to stay, he would have. But Stu quit because he realized he was just a poser and art was where his interests lie.

September 29, 2013 at 8:51 pm

That’s nice, attacking a man when he’s long dead. Were you actually there in Hamburg in 1960-61? If you’ve actually opened your eyes and read the article, and the quotes from people who were actually there (unlike the Stu-hating Saint Paul worshipper fan boys) you would get the impression that Stu, though no rocket-scientist like Saint Paul, could actually play bass. Did you actually read Paul’s quote from 1964? Just goes to show that, great musician though he is, Saint Paul has slowly been trying to re-write history these past 50 years with the passage of time, vilifying Stu simply because he was John’s closest friend. Stu left the band because he wanted to concentrate on his art studies, capeesh? I have gotten over it, I do respect Macca for what he did (musically-speaking), I’m just sick and tired of living guys (like Saint Paul, and yourself) trying to brush over everything and bashing up dead guys (like Stu, John Lennon, Brian Jones, etc.) I personally would take Klaus Voorman’s opinion over yours any day.

P.S-Don’t bother replying, I could do without a troll like you screwing up my Gmail inbox with spam comments.

June 29, 2011 at 3:54 pm

Henry Fool’s colorful comments weren’t sarcastic, they were caustically entertaining…I think the Fool could be a poet.

As for Sutcliffe, he was extraordinary, and if that more-than-established fact offends some people, that’s a problem they’ll have to deal with…

hopefully on their own.

Anybody can discover whether or not Stuart was amazing—all one has to do is check the history instead of ranting. Stamping one’s feet and screaming “revisionist” and “hooey” doesn’t alter facts that anyone truly wanting to know can easily find. Learning about any talented and decent individual is stimulating; digging in and refusing to move is just—stuck.

This article proves to me that Stuart was not a crummy bass player. It doesn’t say he was a phenomenal bass player, it doesn’t say he had no faults, and there are no comparisons made between Stuart’s playing and anyone else’s.

Some Beatles fans are teeth-clenched determined to protect their assertion that only Harrison, Lennon, Starr and McCartney were outstandingly talented…no other genius need apply. That kind of limited thinking shuts out any kind of information, no matter how documented, logical or creditable.

The fact—however uncomfortable to some—is that Stuart Sutcliffe was more than able to stand on his own with or without the Beatles. And when he played bass with them, he apparently was not bad—looks like he was pretty damn good.

July 5, 2011 at 2:48 pm

I know you’re not supposed to believe in everything you read or hear, but OK readers & bloggers; Ok musical snobs & hyper-ventilating, sarcastic “know-it-alls”; unless U R over 70 and YOU were actually there in Hamburg to hear Stu, then 4get your silly notions of what or who Stu was or how he sounded while playing bass. I wish I could’ve been there to hear it too; admit it, so do you! Congratulations if you know how to play bass guitar but quit the snobbery & stop discounting other people’s remembrances of Stu and that special time of Beatles-in-Hamburg lore. Of course McCartney was jealous of Stu (as June babies, their birthdays were days apart); they probably had a bit of love/hate in their relationship as they both competed for Lennon’s attentions at the time & they both had become his best pals in the band. Sir Macca should never have discounted Stu’s talents even in hindsight. And I’m glad Pete Best is speaking up about the topic. He’s been discounted as a good drummer pre-Ringo era. Doesn’t this debate sound familiar? He’s supposed to have been a good drummer w/ a style that’s different from Ringo’s, but just as vital. Man, use your imagination in a positive light: it would’ve been cool if they could’ve had 2 drummers & 2 bass players back then! The “Beat Boys” would’ve been ahead of their time in that mode, but they still evolved into one of the most interesting & innovative rock-acts of all time: The Beatles as we know & love them. So tragic that Stu died & w/ the passing of time, his talent has become questionable. Sadly, the critics will do the same to Pete when he passes on. And who knows what BS the critics will write when Paul & Ringo are dead & gone. It’ll be the end of an era that many people under the age of 50 can’t quite recall and only the elderly past 70 can be certain had ever happened. When it’s all uncertain, you’re simply left with “You shoulda been there”. I miss Motown; I miss the Beatles but the last 5 decades of past history has proven more memorable & influential than some of the crap we’re exposed to in this sophisticated and intellectual internet age of ours. Enjoy yourselves.

September 20, 2011 at 11:55 pm

Thank You!

July 9, 2011 at 5:42 am

Stu was probably an adequate bass player, not different from most bands back then. Just listen to most of the bands that came out Liverpool and London in the very early 60’s. The bass lines were very simple. Paul’s playing was unusually complex, which helped define the Beatles sound. It’s the same as comparing Pete and Ringo. The Beatles sound just wasn’t the same with Pete, but he was good enough to play with most bands from the area at that time.

January 14, 2013 at 5:47 pm

“just same as comparing pete and ringo”? okay, so you are comparing what, oh Sgt Pepper to the beatles Decca audition tapes? Come back someoday when you are comparing Ringo’s drumming from Rory Storm days, as THAT would be an adequate comparison. Ringo had no recording experience and he sorta sucked when we showed up in studio 4/9/62 with barely 2 weeks to learn the originals, yes, originals that the band was recording. If ringo was so much better than Pe , then why did th eband not even tell the producr in advance that they had this OTHER really good drummer they want to bring in next time? The company line is that Ringo was what the band needed, musically. Hardly true, as the band DID have a recording contact in hand, without ringo, and was already the most popular band in Liverpool. Musical ability had nothing to do with why original drummer was sacked. Ringo just was lucky enough to say yes when others said no. Did ringo even ask what happend to his predecessor, and why the drum job was being offered to him in the first place ? Drop your Ringo loyalty for a moment, and question the circumstances. And don’t cite “Love Me Do” on anthology as the reason for sacking, there all other PB drumming tracks are pretty much very alive and driving. Try giving a listen to macca’s voice cracking on that same Love Me Do track from the first test, then come back with some objective commentary.

July 13, 2011 at 10:21 am

Great article! It’s about time we realized that somebody playing for eight hours every night and establishing a strong following in the clubs could not be a poor player. But the author missed one: Gerry Marsden of the Pacemakers, who also played in Germany, said in an interview that Stuart was a “brilliant” bass player! When asked to explain, he said pretty much what Voorman said in this article: that Stu played basic rock and roll and did it very well. Marsden said that kind of hot music was all that was necessary at that time in those clubs, and that Sutcliffe really had it going on.

July 14, 2011 at 2:17 pm

What is most interesting, are the photographs that have surfaced in the Beatles Anthology Book and in various publications, of the Beatles performing onstage in Hamburg with Stuart Sufcliffe facing the audience (sitting on a stool or standing) and singing; and without wearing glasses as well.

July 21, 2011 at 12:55 pm

Speaking of photographs and glasses, I’ve never seen any mention anywhere made of the fact that as soon as the Beatles “made it”, Lennon was consistently photographed wearing dark glasses….just like Stuart used to wear. There are no photographs taken of Lennon wearing shades before Stuart’s death.

July 23, 2011 at 7:23 pm

Quite a fascinating article

July 26, 2011 at 6:43 am

I recently watched an interview with Bob Wooler, DJ/emcee for the Cavern Club. The interviewer straight out asked about Stuart Sutcliffe’s playing, saying he’d heard that Stu’s amp was unplugged because his playing was so bad. Wooler said that was ridiculous and made up by “someone who would remain nameless”. Wooler then said Sutcliffe would sing “Love Me Tender” facing the audience and accompanied only by George’s strumming. Wooler laughed, saying “These are all conceited guys!” Point is, Stuart wasn’t hiding anything from anybody.

To underscore the point, Spencer Leigh wrote of his Cavern experiences, “I remember George Harrison bringing Stuart forward for “Love Me Tender” and the place went wild. They loved it.”.

Unrelated but still interesting: Gerry and the Pacemakers used to be The Mars Bars.

July 27, 2011 at 4:58 am

I love how this article claims to buck the conventional wisdom about Stu and then repeats the conventional wisdom about Paul — blaming McCartney as the sole critic of Stu Sutcliffe’s bass playing. Certainly Paul said Stu wasn’t anything great as a bass player — and Stu wasn’t, compared with McCartney. But I’ve seen countless with George Harrison and John Lennon who also said Stu wasn’t much of a bass player. It was JOHN LENNON who also was pretty relentlessly nasty to Stu, John’s supposed bestest buddy. But by all means, repeat the conventional wisdom about it all being Paul’s fault. He’s an easy target as he’s alive.

It bothers me that Pete Best will say in interviews that he was closest to John Lennon and yet Pete always seems to go out of his way to blame Paul for things. If John Lennon was Pete’s closest friend in the band, then how come John Lennon didn’t even bother to talk with Pete after Pete was canned? And why doesn’t Pete ever blame Lennon for that? I’ll tell you why: Because Pete knows he gets better press by snarking at McCartney and criticizing Saint Lennon wouldn’t go over big.

And I love how some people here turn “Stu wasn’t a bad bass player” into “he was brilliant.” Stu was an average bass player. And to suggest anything otherwise is ridiculous.

September 29, 2013 at 9:04 pm

Yeah, well, it’s not as though any of us actually knew what was going on. Of course Saint Paul would say stuff like that, after all he’s the greatest bass player ever. I’m sure Bill Wyman, Jack Bruce, Noel Redding, John Entwistle and Jaco Pastorius can’t hold a candle to him in terms of bass playing. Good to hear you insulting dead people who did more with their lives than you ever could, posting comments like you actually know everything about the Beatles, Get over yourself. You are definitely a Saint Paul fan boy.

May 30, 2014 at 12:30 pm

But I guess it’s fine for you to insult Paul since he’s still alive?.

The article btw doesn’t even provide much in the way of proof that Paul was so negative about Stu’s bass playing.

June 2, 2014 at 1:51 pm

I actually take my arrogant comment back. I deeply regret insulting Paul. I just don’t believe in the myth that Stu was an average bass player. It’s all about context. Lots of the early British beat bands of the early ’60’s had bass players with rudimentary skills, which by todays standards would be considered average. So long as you could lay down some solid lines, you were good. As time passed, and rock music developed, bass playing became more complex, and this is where Paul comes in. I would delete my previous comment if I could. Paul is a great musician, and the Beatles are awesome.

Peace

Michael

June 2, 2014 at 1:52 pm

By ‘average’ I meant as in plain awful.

August 31, 2023 at 10:15 pm

Or he was a good emerging band bassist. Martin likely would have relaced him in the recording studio as well as Best.

July 27, 2011 at 2:55 pm

How do you get that “some people here” turn Stu into a “brilliant bass player”? The comment said it was Gerry Marsden of the Pacemakers who said that. Since Marsden is British, I figured he used the word “brilliant’ the way lots of Liverpool people do…to mean that he really liked Stu’s playing. If you’re not happy with what those WHO WERE THERE have to say about it, I guess you don’t have much of an option except to get mad.

And what is it with this “turning Paul into a villain” deal? Did you read what Paul said? He called Stuart “a great bass man”. How does that make McCartney a villain? The article said there were two critics of Stuart’s playing. Where do you get the “blaming McCartney as the sole critic”? Did you read the same article I did? Or did all the evidence that Stuart wasn’t a horrendously bad musician just set you off?

I apologize for getting a bit steamed, but this article was not about Paul McCartney. McCartney fanatics fly to Paul’s defense, feeling he’s been attacked when he hasn’t. And I agree with Ali about “sarcastic know-it-alls”—you weren’t there. If you refuse to listen to the statements of those who were, why bother reading at all?

That was pretty nasty stuff to say about Pete Best, who has always been as decent as he could be about the tough deal he was handed. Why all the vitriol?

I think Paul fans hate any hint that Paul was sometimes jealous and insensitive, even though Paul SAID SO HIMSELF in the Beatles Anthology and other places, too.

If you’re determined to ignore eye-witness accounts and stand by the old story no matter what, that’s up to you. You’re entitled to express your opinion— but.you might want to tone down the acidity, finger-pointing and bitter adjectives. Seems somewhat jealous and insensitive.

July 27, 2011 at 3:16 pm

Apologies to Lou…I think I stepped over the line with my last sentence. We are all Beatles fans, no matter which Beatle we love the most. Every one of them, John, George, Stuart, Paul, Pete and Ringo were important to making the Beatles who they were. Each one should be appreciated for his contributions.

September 21, 2011 at 3:39 am

I wasn’t there in Hamburg 1960/ 61. I wasn’t born until ’65! So, I spent 9 years researching and writing my book “Liddypool: Birthplace of The Beatles”. I spoke to those first-hand eyewitnesses, like Pete Best, Howie Casey, Roy Young and many Merseybeat musicians, who told me the same fact: Stu Sutcliffe was a decent bass-player, playing with The Beatles, Howie Casey’s band and The Bats. He also taught Klaus Voorman to play bass. He was a decent bassman. He wasn’t the greatest, and nobody claims he was, and what Paul went on to do with the bass guitar was pure genius. I think we should just acknowledge the true ability that Stuart had and destroy the myths.

September 28, 2011 at 6:26 pm

“Paul has knocked Stu’s bass playing– remarks he made while working with Stu were perhaps spawned by their “dead rivalry” (at least that’s how Paul saw it), and are therefore open to question. But many of Paul’s negative comments have been in retrospect.”

Of course this article is blaming Paul for picking on Poor Saint Stu. Where are the passages where John Lennon and George Harrison both talked about Stu being a weak bass player. Because they both did. No, it’s only Paul that was jealous. Where is the passage about Lennon repeatedly picking on Stu? And of course Saint Stu was never jealous of Paul, or Paul’s relationship with John. That’s what Paul fans mean by the persistent desire to always place the blame of any problem in the Beatles on Paul.

February 26, 2012 at 12:33 pm

One thing people fail to realize or mention is: none of them were probably “great” players back then in 1960-1961. They were all developing. And the musicians the Beatles became were far greater than the musicians they were back Hamburg. All of them were probalby good back then, but not great. And as great as the Beatles songs are, I dont think any of them are mentioned as the best guitarist, bass, drummer or singer in the world. Best songs, best song writers. Best band maybe.

September 29, 2021 at 12:30 am

Please stop with all the uncalled for hateful attacks on Paul. This is a very interesting article to bust the misconceptions about Stuart being a bad bassist during his brief time in The Beatles. He quit the band of his own accord to focus on visual arts, so he was not fired, and perhaps he could have been called on by John to do album covers for them had he lived longer.

In the “Anthology” Part 1, Paul praised Stuart by calling him a very good painter and George did say that Stuart couldn’t play at all when they first met him, but he did learn a few tunes.

The only one who got fired for being an inept musician was Pete Best, hence that Ringo got recruited.

November 7, 2021 at 8:23 am

Where is the article where Gerry compliments Stu’s article? I’d like to see it

April 7, 2023 at 2:56 am

The Beatles were lucky to not have Sid Vicious, as he couldn’t play bass, let alone lead guitar.

June 23, 2023 at 7:50 am

The sentence that was “Is it credible to think that all this learning, experience, confidence and improvement affected every Beatle except Sutcliffe—the others were roaring along, but Stu was still just plunking” tells the most truth. The man was a young artist. His mind was open to new things. I am a bassist and though to be in The Who 1970 you must play really well, to play in a basic 1950’s/60’s style R&R band, “just play the main note” would have been pretty simple for a man like him.

June 23, 2023 at 12:25 pm

I’d give this piece more credence if they knew that “Hallelujah, I Love Her So” was one song, not two.

June 24, 2023 at 4:06 am

🙂A Very well balanced and thoughtful article. Well done!